Roman Family Chiropractic, Pllc, Patterson Road, Grand Junction, Co

The Romans congenital roads over ancient routes and created a huge number of new ones. Engineers were audacious in their plans to join 1 signal to another in as direct a line as possible whatever the difficulties in geography and costs. Consequently, many of the Romans' long straight roads across their empire accept go famous names in their own right.

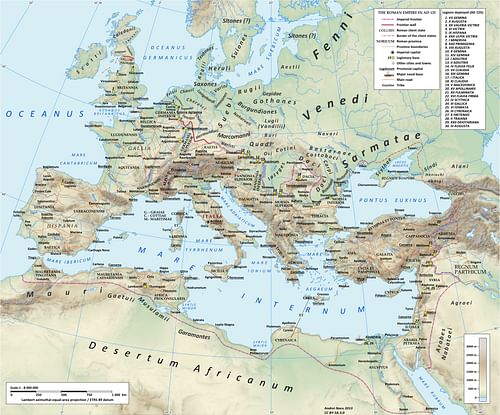

Roman roads included bridges, tunnels, viaducts, and many other architectural and engineering tricks to create a series of scenic but highly practical monuments which spread from Portugal to Constantinople. The network of public Roman roads covered over 120,000 km, and it profoundly assisted the gratis movement of armies, people, and goods beyond the empire. Roads were also a very visible indicator of the power of Rome, and they indirectly helped unify what was a vast melting pot of cultures, races, and institutions.

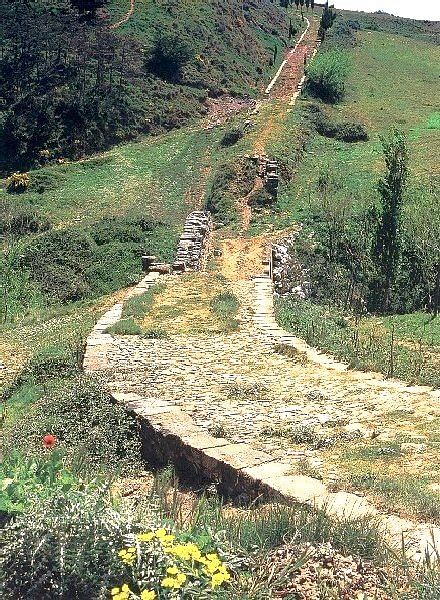

Roman Road, Spain

The Roman Road Network

The Romans did non invent roads, of course, but, every bit in and so many other fields, they took an idea which went back as far as the Bronze Historic period and extended that concept, daring to clasp from it the fullest possible potential. The first and most famous great Roman road was the Via Appia (or Appian Way). Constructed from 312 BCE and covering 196 km (132 Roman miles), it linked Rome to Capua in equally straight a line equally possible and was known to the Romans as the Regina viarum or 'Queen of Roads'. Much like a modern highway, information technology did not become through less important towns along the way, and it largely ignored geographical obstacles. For case, the impressive xc km stretch from Rome to Terracina was built in a unmarried direct line. The road would later be extended all the mode to Brundisium and thus reach 569 km in length (385 Roman miles).

The network gradually spread beyond the empire from Great britain to Syrian arab republic and certain roads became as well-known and well-travelled equally those around Rome itself.

Other famous roads in Italy were the Via Flaminia which went from Rome to Fanum (Fano), the Via Aemilia from Placentia to Augusta Praetoria (Aosta), the Via Postumia from Aquileia to Genua (Genoa), the Via Popillia from Ariminum (Rimini) to Padova in the n and from Capua to Rheghium (Reggio Calabria) in the s, and many more likewise, all with extensions fabricated over fourth dimension. The roads became then famous that they fifty-fifty gave their names to places and regions. The network gradually spread across the empire from U.k. to Syria, and certain roads became as well-known and well-travelled as those around Rome itself. For example, the Via Domitia (begun in 116 BCE) went from the French Alps to the Pyrenees and was invaluable for troop movements in the campaigns in Kingdom of spain. There was also the Via Egnatia (begun in the mid-second century BCE), which crossed the Balkan Peninsula and ended at Byzantium, making it a vital land route between the western and eastern parts of the empire.

To reach the objective of constructing the shortest routes possible between two points (often not visible i to the other), all manner of engineering difficulties had to be overcome. Once extensive surveying was carried out to ensure the proposed road was actually directly and determine what various engineering methods were required, marshes had to exist drained, forests cut through, creeks diverted, bedrock channelled, mountainsides cutting into, rivers crossed with bridges, valleys traversed with viaducts, and tunnels built through mountains. In one case all that was done, roads had to exist levelled, reinforced with back up walls or terracing and then, of form, maintained, which they were for over 800 years.

Roman Road Network

Likewise permitting the rapid deployment of troops and, more importantly, the wheeled vehicles which supplied them with food and equipment, Roman roads allowed for an increase in merchandise and cultural exchange. Roads were also i of the ways Rome could demonstrate its authority. For this reason many roads began and ended in a triumphal curvation, and the imperial prestige associated with realising the projection was demonstrated in the fact that roads were very often named afterward the magistrate official who funded it; hence, for example, the Via Appia takes its name from the censor Appius Claudius Caecus.

Road Design & Materials

Major roads were around a standard four.ii m wide, which was enough space for two wheeled vehicles to laissez passer each other. Roads were finished with a gravel surface sometimes mixed with lime or, for more than prestigious sections such as virtually towns, with dressed stone blocks of volcanic tuff, cobbles, or paving stones of basalt (silice) or limestone. First, a trench was dug and a foundation (rudus) was laid using rough gravel, crushed brick, clay materials or even wooden piles in marshy areas, and prepare between adjourn stones. On top of this a layer of finer gravel was added (nucleus) and the road was and so surfaced with blocks or slabs (summum dorsum). Mount roads might also have ridges running across the surface to give people and animals better traction and have ruts cut into the rock to guide wheeled vehicles.

Roman Route Surface

Roads were purposely inclined slightly from the eye down to the curb to allow rainwater to run off forth the sides, and for the same purpose many too had drains and drainage canals. A path of packed gravel for pedestrians typically ran along each side of the route, varying in width from 1-iii metres. Separating the path from the road, the curb was made of regular upright slabs. In addition, every 3-five metres there was a college block fix into the curb which stopped wheeled traffic riding onto the footpath and allowed people to mount their horses or pack animals. Busier stretches of main roads had areas where traffic could pull over and some of these had services for travellers and their animals too. Milestones were too set up at regular intervals and these ofttimes recorded who was responsible for the upkeep of that stretch of the road and what repairs had been made.

Bridges, Viaducts, & Tunnels

Lasting symbols of the imagination of Roman engineers are the many arched bridges and viaducts still continuing around the empire. From early bridges such equally the Ponte di Mele about Velletri with its unmarried vault and modest span of 3.vi m to the 700 thou long, x-arch viaduct over the Carapelle River, these structures helped achieve the engineers' direct-line goal. The Romans built to last, and the piers of bridges which crossed rivers, for case, were often built with a more than resistant prow-shape and used massive durable blocks of rock, while the upper parts were either built of stone blocks strengthened with fe clamps, used cheaper physical and brick, or supported a flat wooden superstructure. Perchance the almost impressive span was at Narni. 180 one thousand long, 8 chiliad wide and as loftier as 33 grand, it had four massive semicircular arches, i of which, stretching 32.1 yard, ranks as ane of the longest cake-arch spans in the ancient globe. Two of the best surviving bridges are the Milvian bridge in Rome (109 BCE) and the bridge over the river Tagus at Alcantara (106 BCE) on the Spanish-Portuguese border.

Roman Bridge, Pont-Saint-Martin

Tunnels were another essential feature of the road network if lengthy detours were to exist avoided. The most important include 3 tunnels congenital in the 1st century BCE: Cumaea, which stretched ane,000 m in length, Cripta Neapolitano measuring 705 m, and Grotta di Seiano 780 chiliad long. Tunnels were frequently built by excavating from both ends (counter-excavation), a feat which obviously required precise geometry. To brand certain both ends met, shafts were sometimes drilled down from above to check the progress of the work, and shafts could also be used to speed upwards excavation and piece of work at the stone from two angles. Yet, when working through solid stone, progress was tediously dull, perhaps every bit little as 30 cm a solar day, resulting in tunnel projects lasting years.

Conclusion

Roman roads were, then, the arteries of the empire. They connected communities, cities, and provinces, and without them, the Romans could surely not accept conquered and held onto the vast territories they did over and so many centuries. Farther, such were the engineering and surveying skills of the Romans that many of their roads have provided the basis for hundreds of today's routes across Europe and the Middle East. Many roads in Italy still use the original Roman proper name for certain stretches, and even some bridges, such as at Tre Ponti in modern Fàiti, still carry road traffic today.

This article has been reviewed for accurateness, reliability and adherence to academic standards prior to publication.

lapinskiflocruing.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.worldhistory.org/article/758/roman-roads/

0 Response to "Roman Family Chiropractic, Pllc, Patterson Road, Grand Junction, Co"

Post a Comment